|

For more articles like this go to the Look and Learn articles website. |

On a bitter April night in 1898 the largest, most luxurious, and, reputedly, the safest liner in the world, the SS Titan, set out on her maiden voyage from Southampton to New York. She was more than halfway across the Atlantic when the “unthinkable” happened. The 70,000-ton ship struck an iceberg, and foundered. More than half of her 2,500 passengers were lost, partly because there were not enough lifeboats on board.

If the tragedy had happened in real life, it would have caused a public outcry. But the sinking of the Titan occurred in the pages of a short story by a little-known writer, Morgan Robertson. An ex-seaman, Mr Robertson was struggling to make a living as an author in New York. One night in the late 1890s, he fell into a half-sleep in the boarding-house where he was staying, and had a vision which “terrified and elated” him.

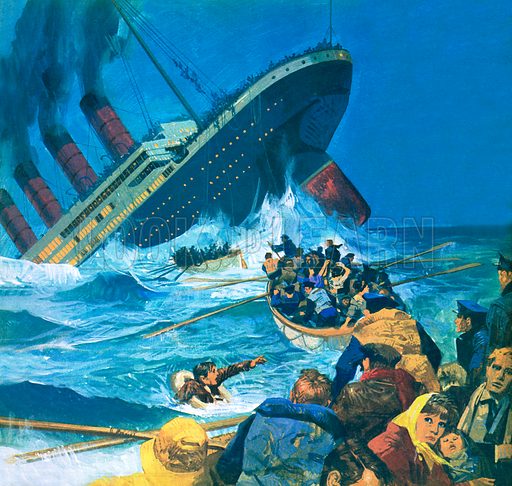

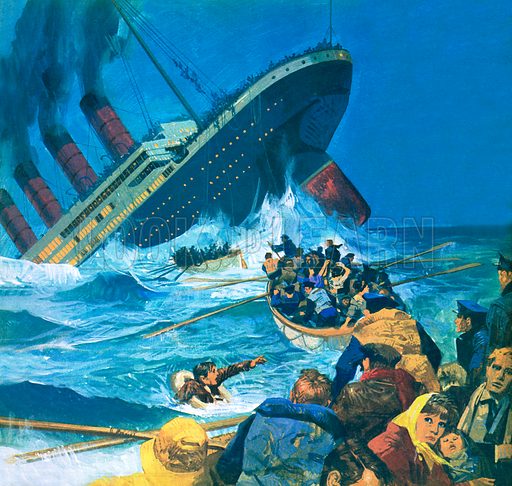

He was terrified because he saw, as vividly as if he had been there, a mighty ocean liner sinking bow-first into the icy and deadly sea. “I could hear the screams of those who were stranded aboard her, and the helpless cries of those who were literally freezing to death in the water,” he stated.

“I woke up still feeling frightened. Then, with the realisation that I had conjured up a marvellous plot, came a sense of elation. I rushed to my desk and wrote the story of the disaster straight out. But the strangest thing was that I didn’t seem to be doing the writing myself. I seemed to have been ‘taken over’ by someone else, a kind of occult being, who wrote the story for me.”

Robertson even claimed that he saw the name Titan on the bow of the ship, and distinctly heard the words “unsinkable” and “April”. He subsequently called his tale The Wreck of the Titan, and it gained respectful, but not very excited, reviews.

Fourteen years later, however, his story was reprinted and hailed as what a New York newspaper called “the most astounding instance of literary prophecy in our time”. For on 15th April, 1912, a real liner, the 66,000-ton Titanic, suffered a similar fate on her maiden voyage to America.

The parallels between fact and fiction were startling. The Titanic weighed only 4,000 tons less than the Titan. Like her fictional counterpart, she was a triple-screw vessel with a top speed of 25 knots. She carried 2,200 passengers, 300 fewer than the Titan, and some 1,500 of them were drowned. As in Robertson’s story, the main failure was the shortage of lifebelts and lifeboats.

The Titanic’s British owners, the White Star Line, considered the liner, with her 16 watertight compartments, to be unsinkable. Their words echoed those of one of the fictitious deck-hands on the Titan, who told a somewhat apprehensive passenger that: “God Himself could not sink the ship!”

Robertson’s story was the nearest that anyone in print came to foretelling the Titanic’s fate. But, oddly enough, he was not the only person to prophesy such a disaster at sea. Some years before the Titanic sailed from Southampton, via Cherbourg, to New York, the well-known British journalist W. T. Stead consulted two fortune-tellers, both of whom warned him against travelling on such a ship, especially in the month of April.

One of them, the celebrated Irish palmist, Cheiro, who had a lucrative practice in London, and included King Edward VII among his clients, told Stead: “I see more than a thousand people, yourself among them, struggling desperately in the water. They are screaming for help and fighting for their lives. But it does none of them any good . . . yourself included!”

Stead told his friends and colleagues about the warning, and pointed out how it tied in with a fictitious article which he had published some time earlier as the editor of a newspaper. The article described a large-scale tragedy at sea, and Stead had added a note stating: “This is exactly what might take place, and what will take place, if liners are sent to sea short of lifeboats.”

He afterwards wrote a magazine article about a liner which sinks after striking an iceberg. And, incredibly enough, he even recorded a dream he had in which he saw himself standing on the deck of a rapidly-sinking ocean liner, without a lifebelt, and with the last lifeboat vanishing into the night. But Stead, a man who privately scoffed at such “irrational and superstitious nonsense”, ignored the omens, and was among those who lost their lives when the Titanic disappeared under the icy waters of the North Atlantic.

However, there was at least one person in Britain who was aware of the predictive power of dreams. He was a businessman named J. Connan Middleton, who, in a letter published in the journal of the Society of Psychical Research in London, recounted an “uncomfortable” dream which made him “most depressed and despondent”.

He had booked a first-class passage on the Titanic in order to attend an important business conference in New York. Ten days before sailing, he had what he later called “an uncanny and unforgettable dream”. He saw the Titanic “floating on the sea, keel upward, and her passengers and crew swimming around her”. He had a similar dream the following night, and told his wife that he seemed to be “floating in the air just above the wreck”.

Still, he tended to dismiss the dreams as the product of his own fears at going on what was, for him, an unaccustomedly long voyage. Despite his wife’s concern, he refused to cancel his booking. Then, just 48 hours before the Titanic was due to sail, he received a cable saying that the conference had unexpectedly been postponed.

“But for that cable,” he said afterwards, “I would have been on the liner in spite of my dreams. I know now that, had I boarded her, I would have been killed.”

Another person who shared Mr Middleton’s good luck was Colin Macdonald, a 34-year-old marine engineer, who was offered the post of second engineer on the Titanic. He turned the job down three times, and in 1964 his daughter told a leading American psychical researcher that her late father had experienced a “strong impression that something awful was going to happen to the Titanic”. The man who eventually took the job as second engineer on the Titanic was drowned.

The final word on the twin disasters of the Titan and the Titanic came from Morgan Robertson himself, interviewed shortly after the actual liner had gone down.

“I only wish I had had my ‘dream of the future’ a little nearer to the Titanic’s sailing date,” he stated. “I don’t suppose anything I wrote would have stopped the maiden voyage from taking place. But it might have scared off some passengers, and so saved at least a few more lives.”