|

For more articles like this go to the Look and Learn articles website. |

To a geologist the word “rock” includes any of the minerals that make up our planet, from granite to the softest clays. In popular usage it is generally applied only to stone; while in American criminal slang “rocks” came to mean the most precious of all stones – the gemstones, and especially diamonds.

In several respects the substance known as diamond is exceptional among minerals. It is the hardest of them all; it has unrivalled lustre; and it is highly resistant to chemical action.

Diamond is one of two forms in which the element carbon is found in the pure, or nearly pure, state in the Earth’s crust. The other is very different in form and appearance. It is the dark grey mineral called graphite, used to make pencil “lead”, and as a fine abrasive in engineering.

Diamond crystals are formed under enormous heat and pressure. The rock in which the diamond is embedded may have come from 150 km beneath the surface.

For centuries the chief source of diamonds was India. Later they were also mined in Brazil, and, in smaller quantities, in other countries, including Russia and North America. In all these regions they are found in beds of gravel, the original igneous rock having been dispersed by erosion.

The richest of all sources of diamonds was not discovered until just over a century ago. This is the famous diamond field at Kimberley, in South Africa. They are now also found in some areas of both West and East Africa.

At Kimberley the first finds were made in loose surface gravel. Beneath this lay a yellowish rock, called “yellow ground”. When miners delved in this, they found it easy to dig – and even richer in diamonds than the gravel. About 15 metres down, the yellow ground ended. Below it was a much tougher rock, bluish or greenish-black in colour, which came to be known as kimberlite, or “blue ground”. Diamonds were equally abundant in this.

The kimberlite is volcanic rock intruded into the earth’s crust from the mantle. The intrusions, known as “pipes”, may be up to 800 metres in diameter. Their depth is unknown, but mining has reached 1,200 metres down or more.

In the Kimberley area, claims were first worked individually. At Kimberley itself, diggings soon undercut the roadways between them. A vast open pit was formed. Conditions were chaotic until the establishment of one big company, which introduced more efficient methods.

The normal practice is to dig vertical shafts some distance from the pipes. From the shafts horizontal galleries give access to the pipes.

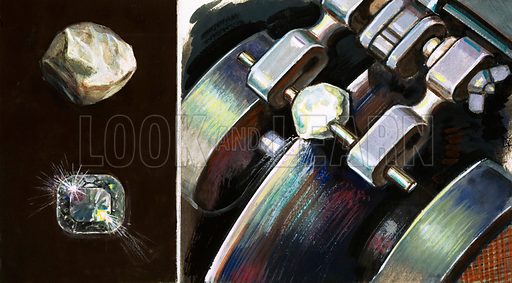

The proportion of diamond to ore is low. Less than 600 grammes of diamond may be obtained from 13,000 tonnes of rock. When first separated from the ore, diamonds appear as dull lumps. Before they are ready for the jeweller, they undergo several processes, during which over half the diamond may be discarded.

The conversion of rough stone into finished gem proceeds through three stages. First it is cut to remove obviously flawed stone and to reduce it to workable size. This may be done in the first place by splitting it, with steel wedge and mallet, across the natural planes of cleavage which exist in the crystal. The commonest crystal structure in diamond is the octohedron, or eight-sided.

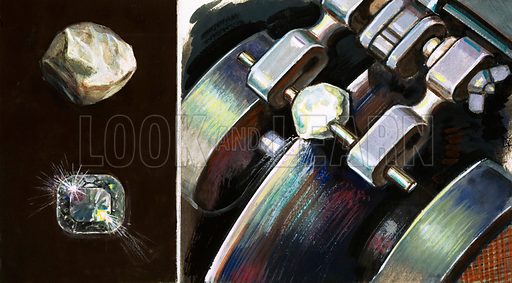

The cleaving stage may be omitted, and the cutting done entirely by sawing. For this a phosphor-bronze circular saw is used, turning at 4,000 revolutions per minute. As only diamond itself is hard enough to cut diamond, the edge of the saw is charged with diamond dust.

Next the diamond is “girdled” – that is, reduced to a cone shape. For this it is turned on a lathe, another diamond being used as a cutter.

In the final stage the stone is given its many facets – in the popular style known as the “brilliant” cut, these are 58 in number. The facets are ground and polished by applying the stone to a revolving disc whose surface holds a mixture of diamond dust and oil.

Diamonds vary in colour, the most valuable being the pure white and the pale blue. A yellowish tint is common.

A large part of the product of diamond mines is used for industrial purposes. Stones unsuitable in size or quality for use as gems are in demand for cutting or drilling hard metals or glass. They are also set in drill-bits employed for boring through hard rock.

As precious stones, diamonds are rivalled by emeralds. These fine green gems are composed of six-sided crystals of the mineral beryl. They are found in veins of limestone which have been metamorphosed by contact with hot volcanic rocks. The best are found in South Africa. They lack the sparkling refractive qualities of diamonds. There are also precious gemstones of beryl with a greenish-blue colour, known as aquamarines.

The bulk of the world’s stock of two other precious stones, ruby and sapphire, come from Upper Burma. They, too, occur in metamorphosed limestone. The rich red of the ruby is due to the presence of chromium, while the sapphire is tinted blue by titanium. Both are formed of the mineral corundum, second only to diamond in hardness.

One other gem is sometimes included among precious stones – the opal. Unlike the others, it is not crystalline, but is formed by simple solidification of jelly-like molten material. Composed of silica, it has many colours, but black opals are the most highly prized.

Click on a picture to find out more about licensing images for commercial or personal/educational use. We are also able to license textual material. Please contact us for details.