|

For more articles like this go to the Look and Learn articles website. |

First came a heavy bombardment of boulders and pebbles, then a thick cloud of fine, white ash. Finally a torrential rain, probably caused by condensing steam, fell to mix with the ash and form a kind of plaster. This plaster was to give a unique but gruesome gift to archaeologists of the future.

The rediscovery of Pompeii occurred in a roundabout fashion. In 1719, builders quarrying marble on the other side of Vesuvius found a treasury of statues. They had stumbled upon Herculaneum, a city destroyed by the same eruption as that which destroyed Pompeii: unlike Pompeii, it had been engulfed in a flow of mud which subsequently turned to a layer of stone 85 feet thick.

The finds were rich, for the people of Herculaneum had been unable to remove their possessions, but the difficulty of working in the solid stone discouraged all but the most dedicated treasure-seekers.

The discovery of Herculaneum reminded men of the existence of Pompeii, however, and search began on the probable site beneath obliterating vines and mulberries growing in the fertile, ashy soil to the south of Vesuvius. It was immediately successful and, because excavating was easier there than at Herculaneum, interest was gradually transferred to Pompeii.

Serious excavations began in 1763; today, over 200 years later, they are still in progress and are likely to continue for many years, for only half the city has been cleared. But this is the more important half, containing the major public buildings.

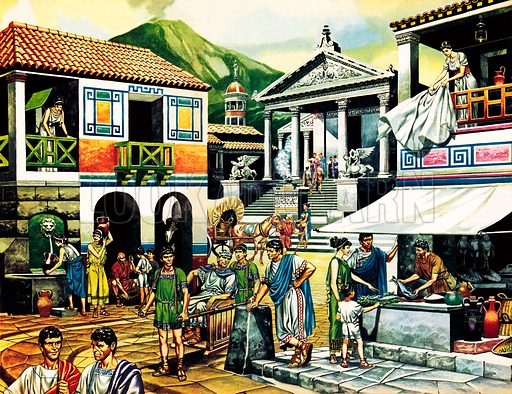

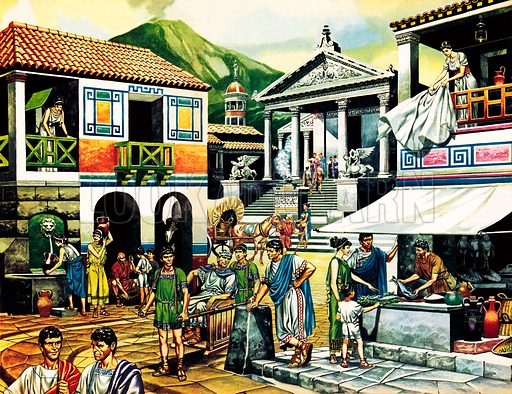

The sudden eruption of Vesuvius had preserved Pompeii, under its layer of plaster, much as it was on that last summer morning of its life nearly 2,000 years ago. The baker’s shop still held loaves of bread – turned now to the consistency of stone but still recognizable; glass containers held what was once fresh fruit; in the tavern the great wine jars stood upright in stalls open to the street; deep ruts caused by wheels in the street showed that Pompeii had its own traffic problem!

In private houses and theatres, temples and baths, the bodies of the citizens lay where they had fallen. The plaster formed by water and ash had made moulds around their bodies, and it proved possible to pour plaster-of-paris into these moulds and so make reproductions of the bodies.

Most of the victims seemed to have taken refuge in buildings in the mistaken hope that the storm would soon pass, but had there been overcome by poisonous fumes or suffocated by ashes.

The death roll was comparatively light, for the able-bodied people who abandoned everything and ran during the first stages of the eruption were able to escape. When at length Vesuvius was quiet again, some survivors even returned to search for their possessions in the 20 ft. thick debris, before abandoning the city altogether.

In the early years of the excavations, the city was ransacked by people hungry for classical antiquities. Walls were torn down for the sake of their beautiful paintings; statues, furniture and personal possessions were taken away to museums or to adorn the villas of the wealthy.

But gradually a more sensible approach brought about restoration instead of destruction and the less valuable objects are now left in the places where they were found.

Pompeii today seems more like a modern city that has been bombed than a 2,000-year-old ruin. The upper stories of buildings were destroyed but the lower were protected; most of the walls stand above the height of a man, so that the streets maintain their ancient appearance. Unlike most famous sites of antiquity, there are mean houses and small shops as well as grand mansions and temples, and everywhere there are the casual evidences of human occupation.

Even the gardens are flourishing again, for their sites have been traced out and re-planted and, with their fountains playing once more, they have brought back a kind of life to the ancient city.