|

For more articles like this go to the Look and Learn articles website. |

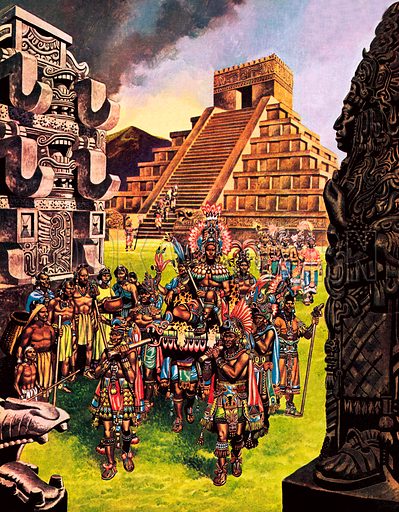

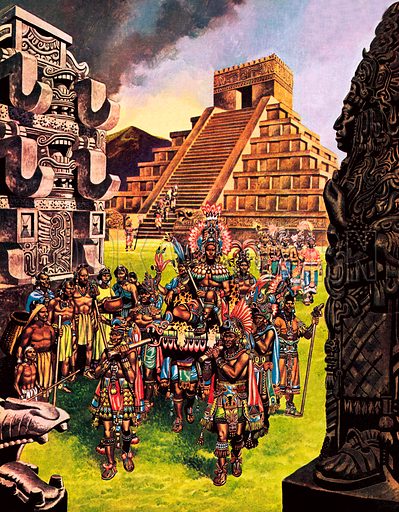

The ancient civilization of Central America is one of the most mysterious in the world, for the people who lived there were unknown to the rest of the world until the 16th century.

Even now, no one knows where they came from. Some believe that they migrated via the Arctic circle, or by boat or raft across the oceans. There are even claims that, originally, they came from the legendary lost continent of Atlantis.

All that can be said with certainty is that these people – the Aztecs, Toltecs and Mayas – were related to each other and created a civilization equal to any in the world.

About the year A.D. 300 the Mayas, for some unknown reason, abandoned their cities in the south and moved northward. Their migration lasted for many years, but they came at length to an area now known as Yucatan, a province of Mexico, and there built cities exactly resembling those they had so mysteriously abandoned.

One of the 18 clans into which the Mayas were divided chose a curious area to found their capital, Chichen-itza. Most cities are founded near rivers, but there are none in this arid district of Mexico, although rainfall is heavy. The rainwater simply percolates through the local limestone and collects in pools underground.

The builders of the city knew this and therefore constructed enormous reservoirs, hundreds of feet below ground, where the water remained cool and sweet.

Like the civilizations of Egypt and Mesopotamia, the Mayas depended upon a complex system of irrigation. The land was thus made fertile at places like Chichen-itza and remained so for hundreds of years – until the coming of the Spaniards in the 16th century.

The Spaniards had expected to find a barbaric country – instead, they discovered cities as great as their own. These they fanatically destroyed, declaring they were heathen and the work of the devil. The natives were disinherited and the land became a wilderness again, for the Spaniards were interested only in gold. The great cities disappeared beneath a sea of vegetation, becoming first a memory and then a legend.

In 1839, a young American, John Lloyd Stephens, with a single white companion, an Englishman called Frederick Catherwood, began to track down the legendary cities. Stephens was a traveller, not an archaeologist, but he had toured the ancient ruins of the Middle East, and therefore knew something of the techniques of archaeology.

Stephens was the leader, but Catherwood, a superb artist, had a very important part to play. At a time when photography was unknown, it was his drawings which proved to an amazed world that the despised “Indians” of Central America were descendants of a mighty race. Even today, some of his drawings show more detail of the fantastically intricate sculpture of the Mayas than do photographs.

Stephens and Catherwood spent some three years in Yucatan and the neighbouring states, discovering no less than 44 great cities. Their task was utterly unlike that which faces most archaeologists, for the ruins they sought were buried not in earth, but in vegetation.

In some places, the forest was so thick that it was possible for acres of ruins to exist half a mile or so from a village and the inhabitants remain unaware of them. All that the explorers could do was to record the existence of the site, leaving others to do the work of clearing it.

Chichen-itza was discovered only a few miles away from one of the oldest Spanish settlements in Mexico. This ancient city proved to be over two miles in circumference, with more than a dozen huge buildings constructed of gleaming white limestone. Dominating the building was a huge pyramid, over 85 feet high, which the native workmen called El Castillo, or the castle.

The discovery of such Mayan pyramids gave rise to a wild theory that their builders had come from ancient Egypt, but the resemblance in shape is purely accidental. The Egyptian pyramid was intended for a tomb, whereas the Mayan pyramid formed the foundation for a temple, with a broad flight of steps leading to the summit.

The purpose of many of the buildings in Chichen-itza is still unknown. A large, rectangular area was probably intended as a place for public athletic meetings, and other spaces are thought to have been used for various ball games. But amongst the buildings were curious box-like structures without windows or doors whose purpose cannot be guessed.

Mayan religion was closely linked to astronomy, and the Mayas therefore developed mathematics to a high level. Their buildings, indeed, have been described as gigantic mathematical symbols, for most of the rich carvings that cover them are the Mayan equivalent of numerals.

Not far from Chichen-itza was a dark, ominous pool, known as the Sacred Well, around which legends had gathered. It seemed that, in the last years of their history, the Mayas had adopted the ritual of human sacrifice. Their neighbours, the Aztecs, slaughtered victims on their pyramids, but the Mayas preferred a different method. At certain times the citizens of Chichen-itza led maidens to the edge of the pool and there hurled them in.

An American, Edward Thompson, one of the many people attracted to Chichen-itza, decided to explore the well, although he had nothing but shadowy legends to follow. His own lively account of the exploration shows that he had cold courage in plenty. At first, he dredged from the bank, but it was difficult to direct operations in the murky water.

At length he and a companion, wearing diving suits, entered the pool.

Though the water was thick and dark enough to hide all manner of monsters, Thompson persisted until he found what he sought. Gold and precious ornaments were brought to the surface, but, mingled with the treasure were the bones of young girls.

Legend had yet again proved to be a good guide.