|

For more articles like this go to the Look and Learn articles website. |

If a visit to the doctor’s in the Middle Ages could be an unfortunate experience for the poor patient, a stay in hospital for surgery until only 150 years ago was still a nightmare beyond the contemplation of many people.

For centuries man had tried with various results but little success to separate the patient’s agony from the surgeon’s scalpel. He had brewed herbs, made wines, inhaled chemicals, pressed upon certain arteries – all in the cause of bringing about unconsciousness before an operation. Sometimes his primitive means of anaesthetizing did reduce the patient’s pain; at other times it succeeded only in adding to it. But it never succeeded in stopping it.

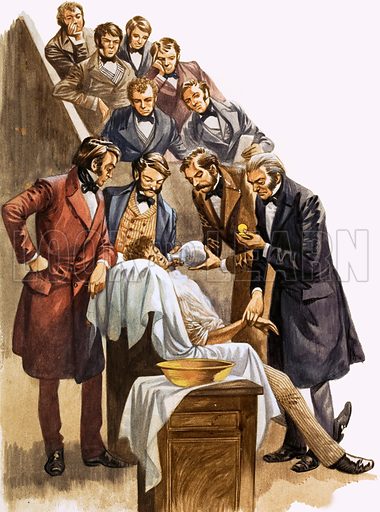

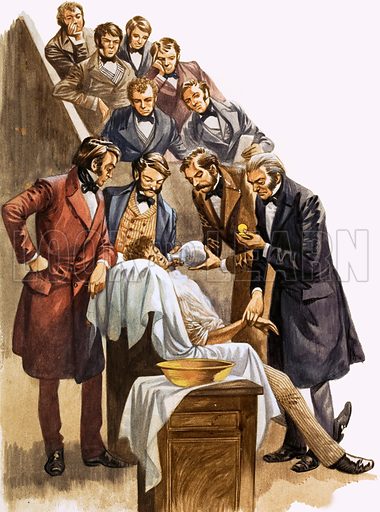

The final conquest of pain with anaesthetics was the work of several men. In 1800 the British scientist Humphry Davy (the same man who invented the miner’s safety lamp) spoke of using nitrous oxide as an anaesthetic during operations. Davy was on the right lines: the trouble was, no one took him up on it. It was not until nearly 50 years later that the anaesthetic called ether was first demonstrated by William Thomas Morton at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

Morton introduced ether into surgical practice under the direction of Dr. C. T. Jackson, who first discovered that by inhaling ether the patient is rendered unconscious of pain.

Other American doctors and dentists had already tried ether with various results, and Morton’s claim of discovery was challenged and argued about. While the quarrels were going on the use of ether spread to Europe. A year after it was used by Morton a Scottish surgeon, Sir James Young Simpson, popularized chloroform as an anaesthetic. Thus the fiercest extreme of medical suffering was stemmed and the surgeon, instead of the patient’s enemy, became his trusted friend.

Pain was killed – but gangrene and blood poisoning were still killing in the wound made by the surgeon’s knife. For 100 years ago antiseptic surgery was still unknown; surgeons still operated in their dirtiest clothes, dressed like butchers, and with dirty hands, because operations were considered messy affairs and there was no point, it seemed, in cleaning up between them!

But in 1862 the French chemist Louis Pasteur announced his theory of fermentation and putrefaction and a British surgeon, Joseph Lister, reading Pasteur’s observations, quickly applied the new theory to his surgery.

The formation of pus in a surgical wound, Lister decided, was due to germs. To us today this is too self-evident for words; but 100 years ago it was a revolutionary idea to consider destroying unseen bacteria in a hospital ward. This is what Lister did: he sprayed carbolic acid in the air around his operating table to attempt to kill the harmful germs.

Today we prevent germs entering an operating theatre rather than kill the ones that are there; we practice aseptic (the prevention of contamination by germs which cause putrefaction) rather than antiseptic (stopping the growth of germs without necessarily killing them) methods, but undoubtedly Lister paved the way to the great benefits of clean surgery, and for his brilliant work he was created a Baron.