|

For more articles like this go to the Look and Learn articles website. |

If you happened to be a keen young knight in 14th century England there was only one place to go, and that was France. France was the home of chivalry, and once across the Channel any ambitious soldier stood a fair chance of making a reputation in the armies of King Edward or the Black Prince.

Today, more than 600 years later, most of us still enjoy reading of the adventures such men had. And if writers are able to recreate that long vanished world of knights and squires, besieged castles and captive fair ladies with astonishing accuracy, it is due almost entirely to the painstaking genius of one man.

Jean Froissart was 19 in 1357, the year in which he plucked up enough courage to declare his love for a young noble woman of exceptional beauty. Unfortunately for him, the girl was not impressed. She not only refused to have anything to do with the “learned clerk” from the Ardennes but actually attacked him, pulling out a handful of his hair.

Historians have had good reason to be grateful to this short-tempered beauty ever since, for in order to forget his unhappy love affair, Froissart began his travels about Europe that were to last the greater part of his life and which were to be the source of his tremendous chronicle.

Froissart was obviously a personable young man, for he seems to have had no difficulty in finding work as a secretary to people of the very highest rank, including the King of France himself. He also wrote long accounts in verse of battles and military campaigns that were much in demand. Considering that the nearest his father had got to the nobility was to paint coats of arms on their shields, young Jean may well have considered himself as a social success, although it’s doubtful if the thought ever occurred to him. No man of action, himself, he had a passion for listening to other people’s experiences and a knack, which has probably never been equalled, of encouraging his fellow men to talk.

When Froissart was about 40 years old, a wealthy friend made him the present of a “benefice”, which meant that he would receive the income of a parish priest for the rest of his life. Froissart might well have disappeared from history at this point, had he not chanced to meet Gui de Blois, one of the greatest soldiers to serve France during those troubled times.

De Blois had been present at the Siege of Calais, and Froissart eagerly wrote down every detail of that famous encounter. When the old warrior discovered that his guest had chests filled with notes on men and battles covering almost all the period of the wars between England and France he was fascinated. Froissart should put them all together and make a great chronicle, he said. Where there were gaps in the story, they should be filled while the people who had actually done the great deeds were still alive.

De Blois knew everybody, and so Froissart started on his travels once more, but this time with a definite goal. One by one he sought out eye witnesses of the great events, and from them he built up an enormous and almost unbelievably detailed story of France in the days when it was the battleground of Europe.

One can imagine his sitting in the great hall of one castle after another, listening and writing as battle-scarred knights remembered aloud what it had really been like at Crecy, of how it felt to be struck by the terrible storm of the English archers, and how the Genoese crossbow men had tried to flee, only to be ridden down by the French knights. Stories of Poitiers, and the capture of King John, with details of the kind of horse he rode, and the name of the knight who took his surrender.

Almost one can hear Froissart’s voice, constantly seeking more and more detail. What did this knight say, or that knight wear? What did they eat and drink before the battle? Why was something done this way and not another?

When Froissart died in 1410 he left a unique picture of the stirring times of 14th century France. And from Shakespeare onwards writers began to draw on this treasure house of information about the great days of chivalry.

Before Sir Arthur Conan Doyle started work on his two great historical tales, Sir Nigel and The White Company, he spent months studying the Chronicles, and a good deal of what readers took to be no more than fiction was really historical fact. Froissart’s book world lives for ever in the great work of reference he created.

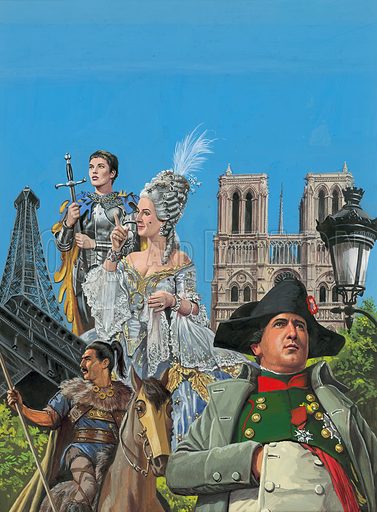

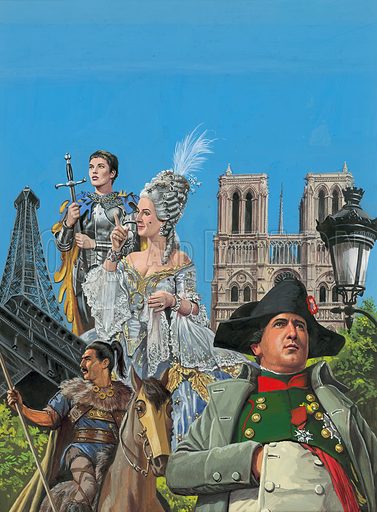

A good deal more than chivalry started in France. With nearly a quarter of a million square miles of the richest land in Europe, it had been fought over countless times, and a natural instinct to close ranks against invaders has resulted in a close-knit people, intensely loyal to their country and often with a deep distrust of change. Yet at the same time, few countries have been quicker to produce new ideas. Revolutionary thinking in politics, science and the arts has resulted in an amazing record of achievement, and there are many people today who consider that the Frenchman’s special blend of imagination and dour, hard-headed practicality has produced the most uniquely civilised country in the world.

There’s a good deal of truth in the saying that the French see no point in travelling abroad, because they can enjoy anything that is worth having in their own country. Travel through France and it is hard not to agree.

In the north are the coal mines, great factories and everything that goes to make up a modern industrial nation. Move southward and the farmlands stretch out to the horizon, almost unbelievably rich and fertile. Still further south and one is among the vines, whitewashed houses and blue skies of the Mediterranean.

Always on the move within their own country the French are used to long journeys, and a northern city dweller is always prepared to drive many hundreds of miles at a weekend to enjoy a day’s skiing in the Alps or the chance to relax in the shade of an olive tree in sunny Provence.

France really is story book country. Most of the great fortresses visited by Froissart are still there, and it doesn’t take much imagination to picture the knights, mounted on their great chargers, riding out across the drawbridges to do battle with the Black Prince. If you visit the little town of Crecy, near Abbeville, you can see not only the battlefield but the ruins of the mill in the shadow of which Edward II watched the fighting. The field of Agincourt is so unchanged that the single building, an inn, shown on maps of the period, is still there.

It doesn’t matter if you’re not particularly interested in the days of the English bowmen, France can always offer something to stir the imagination. Drive along one of the seemingly endless straight roads, and you find yourself remembering that the tall trees were planted on either side of it to shelter Napoleon’s marching soldiers from the sun. You can explore the ruins of a Roman theatre, discover how wine is made or discover an abandoned gun emplacement overlooking the beaches that made history on D-Day.

Because history seems so alive in France, it’s something of a shock to come upon a huge nuclear power station or stare up as Concorde sweeps overhead on a proving flight. But it makes you realise that the kind of men who built the cathedrals of Chartres and Notre Dame, the marvellous roads and canals and towering mansions have lost none of their old skills and are thoroughly at home in the 20th century.

The French are a very logical people and do not expect to get anything for nothing. By our standards, even the schoolchildren work very long hours, and new buildings seem to grow with incredible speed. But at the end of each day there can be few countries where people relax with such enjoyment. After all, the French will point out, they have every right to smile. They live in France.